Microalgae don’t look like much – and I mean that literally. Microscopic forms of algae, formed of unicellular species, they’re invisible to the naked eye. Even larger examples only come in at a few hundred micrometres, barely four times the diameter of a human hair. Unlike larger plants, meanwhile, microalgae don’t have anything as complicated as roots, stems or leaves, instead subsisting in salt or freshwater, gaining the nutrients they need from the sun.

With such tiny proportions, at any rate, it makes sense that serious cultivation of microalgae only began in 1890. It would be a mistake, however, to let their size deceive you. Scientists estimate, after all, that over 200,000 species of microalgae exist on Earth, with a remarkable 72,500 consistently catalogued. Nor does the variety end there. Rich in essential amino acids, vitamins, minerals and more, they enjoy remarkable nutrient density. It goes without saying, that these characteristics are being put to good use: from 2024 to 2032 alone, the global microalgae food sector is expected to grow to $1.2bn, along the way enjoying CAGR of 8.6%.

All the same, it’d be wrong to imply that the microalgae revolution is assured. For if they can now be found in chocolates and beverages, and in more traditional supplements too, they may also come with a range of negative side effects – especially for the most vulnerable people in society. Then there’s the question of research, with long-term human trials still notable by their absence. All of a sudden, the future of supplemental microalgae suddenly seems rather less certain, even if their potential is ultimately too helpful to ignore.

Rich sources

How to describe microalgae’s ascent in the ingredients space? Listen to Xinyu Duan and the answer could plausibly be characterised as ‘slowly, then quickly’. Initially, explains the doctoral student and microalgae expert at the University of Melbourne, these algae were viewed merely primarily as components of aquatic ecosystems – “but research in the late 20th and early 21st centuries began to reveal their potential as sources of nutrition and bioactive compounds”. From there, Duan continues, scientists like her have uncovered their “rich content” of proteins, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. “These discoveries,” she adds, “have spurred interest in microalgae for their potential to combat malnutrition, improve health and treat various diseases.”

It’s hard to disagree, and not just because of those headline growth figures. “Today,” notes Eduardo Jacob-Lopes, a professor at the Federal University of Santa Maria in Brazil, “commercial facilities for microalgae production are scattered worldwide.” Certainly, it’s a point echoed right across continents. Based in Edinburgh, for instance, MiAlgae recently announced installation of eight new bioreactors, allowing for the production of hundreds of tonnes of nutrient-rich microalgae powder. In 2020, for its part, Portuguese manufacturer Allmicroalgae unveiled plans to ramp up production of its own microalgae products by 50%.

On one level, this bewildering growth can be chalked up to Duan’s “rich content” – all those health-giving vitamins and minerals that microalgae are so rich in. But that hardly explains their sheer abundance, with some estimates suggesting that their photosynthetic activity generates half of global oxygen. For Jacob- Lopes the answer arguably lies in their adaptability. “Microalgae,” he explains, “is a bioresource that is extremely resistant to adverse conditions. This arises from a characteristic called metabolic plasticity. Metabolic plasticity is the ability of an organism to use more than one metabolism to survive. Most living beings use only one metabolic route to obtain energy. Some microalgae, like cyanobacteria, can use up to three metabolisms simultaneously – and this is a unique difference in nature.”

Toxic traits

If that explains the microalgae’s longevity, their practical benefits are no less striking. Consider, by way of example, chlorella. A green freshwater alga, it’s renowned for its high chlorophyll content and robust nutritional density. Packed with proteins, vitamins, minerals and omega-3 fatty acids, it’s increasingly popular as a dietary supplement. Once again, the numbers here are stark: according to work by Meticulous Research, the chlorella market is expected to reach $640m by 2031. Like with metabolic plasticity, meanwhile, chlorella may have more unusual benefits. One, says Duan, centres around detoxification, particularly given it may be able to bind to and remove heavy metals from the body. “Additionally,” Duan adds, “its high antioxidant content may contribute to overall health by combating oxidative stress.”

200,000+

The number of scientifically known microalgal species.

Algal Research

Nor is this freshwater alga alone – with many other microalgae showing similar potential. Dunaliella salina, for instance, is a saltwater microalga known for its high beta-carotene content. Because betacarotene is a precursor to Vitamin A, and a powerful antioxidant, this plausibly means it offers significant benefits for eye health and vision. Then there’s Haematococcus pluvialis, a prime natural source of astaxanthin, itself boasting increasing evidence of anti-inflammatory properties. Spirulina, for its part, is known for its high protein content, meaning it may lower blood pressure and cut cholesterol.

$1.2bn

The predicted size of the microalgae food sector by 2032.

Fortune Business Insights

If all this goes much of the way towards explaining the buoyant global market for microalgae, Jacob- Lopes pinpoints another factor too: its suitability for vegans. As the Brazilian explains, the typical vegan diet struggles to contain enough protein, with vegetable sources typically containing less than 20% protein. Once again, however, the strange and impressive makeup of microalgae seems to save the day. As the professor says: “Spirulina can reach incredible levels of 70%. In addition to the absolute content, the amino acid profile – which are the individual molecules that make up the protein as a whole – is complete, covering all essential amino acids for humans.” With these figures in mind, at any rate, the vegan microalgae sector is soaring as well, with Nestle alone investing $1.2bn in regenerative agriculture like microalgae.

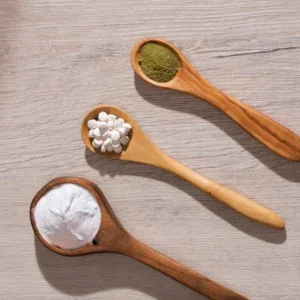

That, of course, still leaves the question of how people are actually absorbing all this microalgae. To a certain extent, intake comes from the usual suspects. To quote Jacob-Lopes: “The most traditional form of consumption is in the form of whole-dried biomass, in the form of tablet, capsule or powder.” Yet as the focus on vegan diets implies, that’s shadowed by a plethora of more innovative methods too. “For those who enjoy cooking,” notes Duan, “microalgae powders can be incorporated into homemade energy bars, mixed into salad dressings, or used as a seasoning for soups and salads. Some adventurous cooks even use them in baked goods like breads or muffins, adding both nutrition and a unique colour.” Then there are efforts by the commercial food firms like Nestle, with microalgae pasta, protein bars and even ice cream all available in shops.

Given all its strengths, should we expect to be enjoying microalgae diets anytime soon? Perhaps not. One problem, both experts agree, are the potential side effects. “People with autoimmune diseases should consult a healthcare provider, as some microalgae might stimulate the immune system,” warns Duan. “Pregnant women should also consult their healthcare provider before consuming microalgae supplements. Those with seafood or iodine allergies should be cautious. Some microalgae can interact with certain medications or affect blood clotting.” Jacob-Lopes, for his part, notes that depending on the species, some microalgae have toxins, which could obviously limit their use.

To be sure, there are ways forward here. When, after all, the quality and purity of supplements are so important to avoid contamination risks, consumers can be careful about which products they ingest. Regulations clearly help here too, with 2024’s EU Novel Food Status Catalogue meaning that several species of microalgae are now permitted to be sold as food or supplements across the bloc.

Perhaps a larger challenge, rather, is one that blights so much of the ingredients space: the lack of scientific consensus on what microalgae can do. For if their potential is clear – how could it not be, given all those vitamins and minerals – research has been blunted by vague and inconsistent results. As Duan says, while “initial studies” are certainly promising, more robust trials are needed – especially large-scale ones involving animal and human subjects. Jacob-Lopes makes a similar point, conceding that securing regulatory approval “for producing speciality chemicals from microalgae” remains challenging.

Despite these stumbling blocks, however, you get the sense that microalgae are irresistible. “As global concerns about sustainability, food security, and environmental impact intensify,” Duan argues, “microalgae are likely to play an increasingly important role. We can expect to see advancements in cultivation techniques, making production more efficient and cost-effective.” That, the doctoral student adds, will inevitably lead to lower prices for consumers, yet another boon to this burgeoning industry. Who knew something so small could pack such a punch?