We all need sleep – but we don’t all get it. Especially since the pandemic and the schedule-ravaging implications of lockdowns and remote work, more and more people across increasing swathes of the Western world are fighting to get enough shut-eye. As so often, this is dramatically clear from the statistics. According to one recent study from the Sleep Foundation, for example, one-third of US adults enjoy less than the seven hours of sleep they need each night. Even more strikingly, a significant minority of Americans appear to suffer from actual sleep disorders, up to 70 million according to one estimate. Europeans, for their part, appear to suffer from related problems.

In the UK, 36% of adults claim they struggle to fall asleep at least once a week, with a fifth facing problems each and every night. Beyond the immediate impact of Covid – a recent paper published by the National Institute notes it reduced sleep quality for many – these issues can arguably be understood as reverberations of modern life. From an over-dependence on smartphones to the stresses of nine-to-five schedules, there are plenty of culprits here, even as the societal impact of sleepless nights extend far beyond the blearyeyed individuals themselves.

In the US alone, so-called ‘drowsy driving’ is responsible for over 6,000 lethal accidents each year. Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, Germans apparently lose 209,000 days of productive work a year thanks to a lack of sleep.

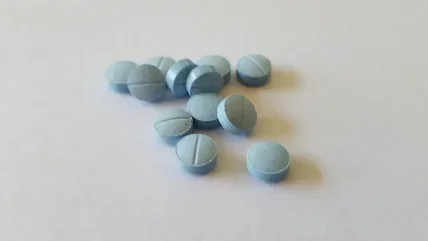

Given all this, at any rate, it should come as no surprise that punters are eager to find ways to sleep better – with supplements, ranging from melatonin to lavender, an increasingly popular solution. Yet if the sector is obviously booming, questions remain around their efficacy. The placebo effect, after all, probably drives the reputed success of some products, even as the usefulness of others remain unclear. Then there are educational challenges around what ‘supplements’ actually are. If some envisage them as a kind of sleep-inducing aspirin, they’re sure to be disappointed. Sleep is too innate, too complex a process for that, and arguably requires more fundamental lifestyle changes to truly see improvements.

Give it a rest

There’s no doubt that sleep supplements are having a moment. According to work by Precedence Research, for instance, the global sleep aids market was already worth $78bn in 2022 – a figure expected to explode to $131bn a decade later. That’s echoed by the rise of particular supplements. To give one example from research performed by Mayo Clinic in 2000, 0.4% of Americans said they artificially used the hormone. By 2018, that figure had increased to 2.1%.

To an extent, argues Dr Michael Grandner, this enthusiasm can be understood in terms of the problem supplements claim to remedy. As the director of the Sleep and Health Research Programme at the University of Arizona puts it: “A lot of people identify that their sleep is deficient in some way – and they want to fix that.” As far as supplements in particular are concerned, moreover, Grandner argues that many users may view them as gentler alternatives to proper medications, such as sedatives like Valium that simply knock you out.

Fair enough: one 2019 poll found that 86% of Americans take a supplement, a figure far higher than those that pop proper pharmaceuticals. In practice, however, the actual helpfulness of such products is disputed. Valerian is a good example here. As a popular plant-based sleeping supplement, some studies have indeed shown that it beats a placebo at calming part of the brain and could ultimately help fight insomnia. On the other hand, and as Grandner points out, those successful tests have tended to be “smaller and uncontrolled”. In part, this lack of clarity stems from the industry itself. With competition so fierce and potentially lacking either legal or scientific knowledge – or simply sufficient scruples – Grandner suggests that especially smaller manufacturers sometimes overegg their claims. Doctors, for their part, may know little better, relying mainly on vague memories of what supplements do from medical school.

More generally, though, you get the sense that the real misunderstandings around sleeping supplements are formed by users themselves. For if they clearly imagine them as safer and less habit-forming than pharmaceuticals, surveys also point to the fact that many view them as ersatz drugs, offering a clear and notable effect once taken.

“A lot of people identify that their sleep is deficient in some way – and they want to fix that.”

Yet as the name implies, ‘supplements’ are simply there to bolster what the body should naturally be doing already. In other words, supplements are not like paracetamol and a headache, where taking one will immediately start alleviating the other. “Sleep isn’t one thing,” is how Grandner summarises the situation: “It’s lots of these systems – that are built over thousands of generations of evolution.”

6,400

The number of lethal accidents in the US each year caused by ‘drowsy driving’.

National Sleep Foundation

Bitter pills

With these subtleties in mind, how can we begin re-evaluating what sleep supplements can do in reality? Melatonin is a good place to start, and not merely because it’s the most popular sleep supplement by far. Naturally occurring in the pineal gland of the brain, Grandner says that it’s there to “tell your body when it should start getting ready for sleep”. For that reason, ingesting a lot of melatonin during the day, when the body isn’t expecting it, isn’t going to do much. On the contrary, Grandner recommends small doses a few hours before bedtime. Too much, he says, risks messing up the sleep cycle and rendering users sleepy even the next morning. “A low dose melatonin relatively early can help shift your [sleep] curve – but it doesn’t change your sleep.”

“A low dose melatonin relatively early can help shift your [sleep] curve – but it doesn’t change your sleep.”

In short, melatonin seems like a safe bet for people who battle to get to sleep occasionally or are looking to start their rest cycle earlier. Crucially, however, it is ineffective for sufferers of so-called insomnia disorder. Unlike sporadic light sleep, insomnia disorder is a diagnosable medical condition, whereby sufferers struggle to initiate or maintain sleep at least three nights a week for at least three months, and where their daytime functioning is drastically impacted as a result. More to the point, insomnia disorder has little to do with melatonin or the lack thereof. At its root is a psychological problem – sufferers tend to become stressed about the very act of sleeping, a worry that worsens as time goes on – and instead Grandner suggests that insomnia disorder is best tackled via cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

209,000

The number of productive days lost due to lack of sleep in Germany.

RAND Europe

To put it differently, the endless debates about the efficacy of melatonin risk missing the point. Neither a miracle hormone nor mere snake oil, what really matters is what it’s used to treat. You could plausibly say something similar about other sleep supplements too. Magnesium, for instance, does have properties that apparently quiet down brain cell activity and relax muscles. But if that might calm nerves, it’d be wrong to call it sleepinducing in the same way as a Valium. It’s the same story, Grandner adds, with valerian and camomile. “The molecules in it should presumably cause some sedation,” he says, “but they don’t seem to fix sleep problems.”

Sleep on it

While sleep supplements – when taken with sufficient care – can certainly contribute to more restful evenings, it seems clear that the story is far more complex. Not that this should be particularly surprising. Central to the evolution of life on Earth for literally millions of years, Grandner notes that even creatures like fruit flies have “shockingly similar” circadian rhythms to humans. Trying, therefore, to shape a force as elemental as sleep with tools as blunt as sleep supplements is probably a waste of time – or anyway a bad idea. “If you want to drag yourself kicking and screaming into unconsciousness – whether you like it or not – we can do that, but it’s going to come with negative effects,” is how Grandner vividly explains it.

That’s undoubtedly true. Quite aside from their efficacy, there’s rising evidence that even supplements like melatonin can sometimes come with unpleasant side effects, ranging from stomach aches to nausea. And that, of course, is before you consider the more dangerous risks of actual sleeping pills, with older users especially likely to suffer falls, often resulting in injuries like broken hips. It hardly seems unreasonable, therefore, to consider more holistic ways to get enough sleep.

As Grandner says, CBT can be particularly valuable for sufferers of insomnia disorder. For less serious cases, the old clichés really do apply. According to a trio of Swiss researchers, for instance, the blue light emitted from smartphones and laptops may well prevent young adults from sleeping soundly. Heavy meals and alcohol can be detrimental too, even as regular exercise can spur shuteye as evening falls. That’s not to say that melatonin or any other sleep supplement is entirely useless. But as with so many other modern health problems, lifestyle matters too, whatever pills you’re taking.