The American Bar at the Savoy in London has a long association with the martini. The first recipe was published in The Savoy Cocktail Book by head bartender Harry Craddock as long ago as 1930; more recently, a Savoy dirty martini was created by current bartender Giannis Sitanos. This drink should be made with vodka, vermouth, the Savoy’s own bitters and a couple of muddled olives, but something is unusual: the central element – the vodka – does not hail from Russia or Poland, but the rolling countryside of West Dorset, and is distilled from whey.

Black Cow vodka is not the only example of whey being used in applications that are at odds with its recent iteration as a protein supplement. In Ballyvolane, Ireland, a gin named Bertha’s Revenge – Bertha being a cow that lived to 49 and featured in the Guinness World Records – is also made from whey. Elsewhere, artisan bakery Bread and Loaf used whey from cheesemakers Appleby’s to produce their awardwinning Shropshire Whey bread.

Uses beyond the gym

Whey’s change in image is reflected in its position on food industry reporter Datassential’s list of trends to watch in 2018, featured alongside black garlic, labneh and salt curing. The report highlighted the ingredient’s use in chef Sarah Grueneberg’s cult pasta dish Cacio Whey Pepe, served at Monteverde restaurant in Chicago, as well as its appeal to consumers looking for healthy options, as high-protein diets increase in popularity. Whey is now not only mainstream, but also fashionable.

For Fraser Tooley, president of the European Whey Processors Association (EWPA), this is the inevitable culmination of significant work done by the dairy industry.

“It’s been gaining momentum over recent years and now it’s reached a certain critical mass or volume,” he says. “All of the hard work that we’ve been doing in promoting and supporting at conferences, universities and shows is all paying off now, as people understand the value and the versatility of this product.”

Whey is produced during the process of making cheese from milk; the addition of rennet or acid to heated milk causes it to curdle and split into the curds and whey of Little Miss Muffett fame. When strained, the solid curds are used to make cheese, leaving the liquid whey.

“You need about 10L of milk to make 1kg of cheese and 9kg of whey,” Tooley explains. “So, whey was a huge by-product of cheese production, and was – in the first instance – fed to animals because it’s an extremely good protein.”

While whey is still used as animal feed, its myriad alternative uses are being increasingly recognised. This is, in part, due to the complex composition of whey, which is made up of constituents including protein; lactose; amino acids and peptides; minerals; and elements such as calcium, potassium and sodium.

“Whether it’s pharmaceutical, nutrition, animal nutrition or food structure, there are hundreds and hundreds of applications for the diverse components of whey,” Tooley says.

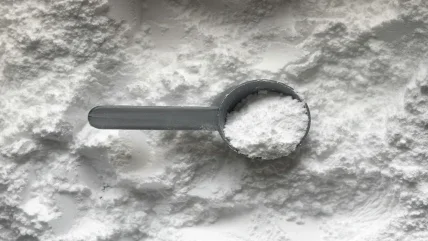

Filtration and drying processes are employed to produce whey protein isolate (WPI), often found as a nutritional supplement to build muscle mass and aid in recovery after exercise. This is perhaps the most well-known use of whey, but it has also served to make it a household name and facilitate its integration into other markets.

“We’ve gradually moved whey into the nutrition sector, and into the sports or the performance lifestyle nutrition sector,” Tooley says. “People and companies use whey as their source, and they advertise this and they promote it, so it’s gradually grown in the public’s perception.”

It’s this growing presence of whey in premium and artisan food products, on restaurant menus and in everyday supermarket items, that has propelled it on to Datassential’s list.

In some cases, this means a return to traditional practices. Whey butter – also known as farm or after butter – is made by separating out the cream remaining in whey and is listed by Slow Food in the UK as a ‘forgotten food’. Nevertheless, its popularity seems to be rising: it can be bought from artisan creameries such as Quicke’s in Devon, and is made and served at Le Suquet restaurant in France, holder of the maximum three Michelin stars until head chef Sébastien Bras declined them this year.

Other products have taken the results of modern processing from the gym and into the shops. WPI is a key ingredient in low-fat ice cream Wheyhey, which is stocked in supermarkets and touted as a healthier alternative to standard ice cream for a range of consumers. “This is a mainstream lifestyle product which belongs in the freezer aisle [and] not the supplements section,” co-founder Greg Duggan told The Telegraph in 2014.

Nothing goes to waste

Whey’s rise in popularity means that what was once a waste product of the cheese industry can no longer be considered in such terms. “The dairy industry has had, over the past 50 years, a history of looking at its co-streams and adding value to them,” Tooley adds. This is the case, for instance, with skimmed milk powder; after milk is separated during the process of making butter into cream and skimmed milk, the latter can be spray-dried to create a product with a long shelf life and uses in various products, such as confectionery and bakery items. “By adopting new processes and technologies, we are able to bring to value virtually all of the milk and whey components,” Tooley states.

In fact, whey’s trendiness and range of uses means that it cannot truly be considered a co-stream, but more of a primary product for the dairy industry.

Tooley explains that the requirements and standards for whey production are now driving the set-up of new cheese factories and the cheese products they produce. “[The dairy industry is saying], ‘This is the whey we want, this is the quality we want, these are the standards we want – you will therefore build a cheese factory like this.’ And that’s driving change and innovation in cheese as well.”

Acid whey

While the whey under discussion so far has been the sweet variety created in cheesemaking, the whey produced in the manufacture of Greek yogurt has made headlines because of its potential impact on the environment. This product is widely referred to as ‘acid whey’ due to its low pH; however, there is potential for confusion in the terminology, as ‘ acid whey’ can also describe the cheese whey made when a reduction in pH is used to separate out the curds. The composition of yogurt acid whey is notably different to the sweet kind.

Unlike this type, yogurt acid whey contains only small amounts of protein. “A lot of the valuable components have already been utilised,” Tooley explains. “Its value is lowered, because it has a different component structure, and what’s left is mainly lactose and minerals.”

While there are now numerous uses for sweet whey, the problem of what to do with the excess acid whey produced in yogurt making still confronts the dairy industry. If dumped, it can cause significant damage to the environment, with bacteria feeding on the lactose it contains depleting oxygen supplies in waterways.

Acid whey is a particular problem in North America, where Greek yogurt production has boomed. It is often incorporated into animal feed, but supply is outstripping demand.

New York-based yogurt company White Moustache markets its leftover whey as a healthy and upmarket probiotic drink and frozen-probiotic pops in a variety of flavours, emphasising the calcium and other nutritious elements present in the whey. Such a move suggests this co-stream may undergo the same shift in image that is currently being achieved by sweet whey.

While the EWPA deals with sweet whey – which is still the vast majority produced of this ingredient – Tooley is optimistic that the industry will find a solution to the acid whey surplus. “The dairy industry will resolve it, because we have a track record of resolving all these issues, saying, ‘Oh right, here’s a co-stream, what are we going to do with it?’” he affirms.

Health kick

The industry’s capability to find new and varied uses for sweet whey is set to increase as research points to the plethora of health benefits associated with the ingredient. In 2015, a research paper published in the Journal of Food Science and Technology highlighted investigations into the potential benefits of whey protein in the treatment of diseases – including cancer, diabetes and obesity – and the improvement of gut health.

Tooley points out the role whey could play in diet and the health of the large intestine. “I expect this to be an area that is going to attract more interest, more research, more understanding, more products and more innovations in the coming years,” he comments.

The ability to use whey to this end is also being facilitated by evolving technology. “There’s a lot of downstream technologies emerging and being developed as well – enzyme technologies – to further process the whey components into valuable new ingredients,” Tooley adds. The use of enzymes on whey protein concentrate increases the content of peptides – proteins – which are important for overall health, including hormone production and the functioning of the gut.

In the meantime, the EWPA and the European dairy industry face a pressing concern: the UK’s departure from the EU. “Brexit’s going to have an effect on all agricultural industries, and any agricultural product that is moving to and from the UK has the potential to be affected,” Tooley points out.

The industry will have to hope that Brexit will not stymie this growth by creating a barrier to the integrated and efficient supply chains it has cultivated, as interest in whey booms and its use continues to diversify.